Understanding the Y combinator

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

This article is about the Y combinator, a fixed-point combinator that provides a way of using recursion in scenarios and programming languages where symbols are not available. The concept of the Y combinator itself is closely related to lambda calculus (λ-calculus) and functional programming languages. More information on this topic can be found on my article about Understanding Church numerals.

For the examples and code snippets in this article, the Scheme programming language will be used, which is a dialect of Lisp. However, since most people are more familiar with the JavaScript syntax, and it is able to express the same concepts, it will also be used whenever possible. Lastly, some lambda calculus notation is used, which is explained in detail in my previously mentioned article.

This article was heavily inspired by Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs (SICP), a book by Harold Abelson and Gerald Jay Sussman. The book teaches the fundamental principles of computer programming, including recursion, abstraction, modularity, and much more. Section 1.3.3 of this book covers the topic of finding the fixed points of functions, which was the main motivation for this article. I strongly recommend, specially since it has a modern JavaScript version1 for those who are not interested in Lisp.

2. Simple example: Factorial

This is the function for calculating the factorial of a number \(n\), using the lambda calculus notation:

\[ \text{fact} = \lambda n. \Big(\Big(\text{iszero}\ n\Big) 1 \Big(\text{mult}\ n \ \big(\text{fact}\ (\text{prec}\ n)\big)\Big)\Big) \]

In Scheme:

(define fact (lambda (n) (if (equal? n 0) 1 (mult n (fact (prec n))))))

Or in JavaScript:

var fact = (n) => (n == 0) ? 1 : mult(n, (fact(prec(n))));

We are defining fact as a function that takes a parameter n. This function

returns 1 if n is zero, and otherwise multiplies n by the factorial of the

number preceding n.

In this case, we can simply ignore how iszero, mult, prec and even fact work

internally, we just have to trust that they do what we expect. Another useful

way of thinking about lambda calculus and Lisp in general is as a language for

expressing processes.

In any case, we don’t have those name-defining commodities in lambda calculus. A function can’t call itself by name, so we will have to find an alternative way.

3. Simple recursion with anonymous functions

Before trying to understand the Y combinator, let’s have a look at an example of how an anonymous function might call itself without the need for symbols.

\[ (\lambda x. x\ x)(\lambda x. x\ x) \]

Or in Scheme:

((lambda (x) (x x)) (lambda (x) (x x)))

Note: Depending on the Lisp, you might need to use

(funcall x x)instead of(x x), since variables and functions don’t share the same namespace. You can search about the differences between Lisp-1 and Lisp-2.

Or in JavaScript:

((x) => x(x))((x) => x(x))

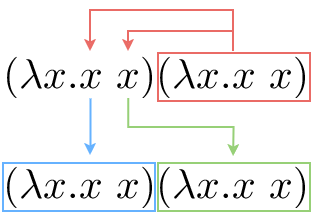

We can see that the two parenthesized expressions are identical, and that the first is applied to the second one. Let’s try to simplify it by β-reduction. The first parenthesized expression, is applied to the second one. We replace each occurrence of \(x\) in the body of the first expression with the whole second parenthesized expression.

We are right back where we started. This function would call itself indefinitely, and a similar form will be used for the Y combinator below.

4. Fixed points

Before getting into the fixed-point combinators, we need to define what a fixed point is.

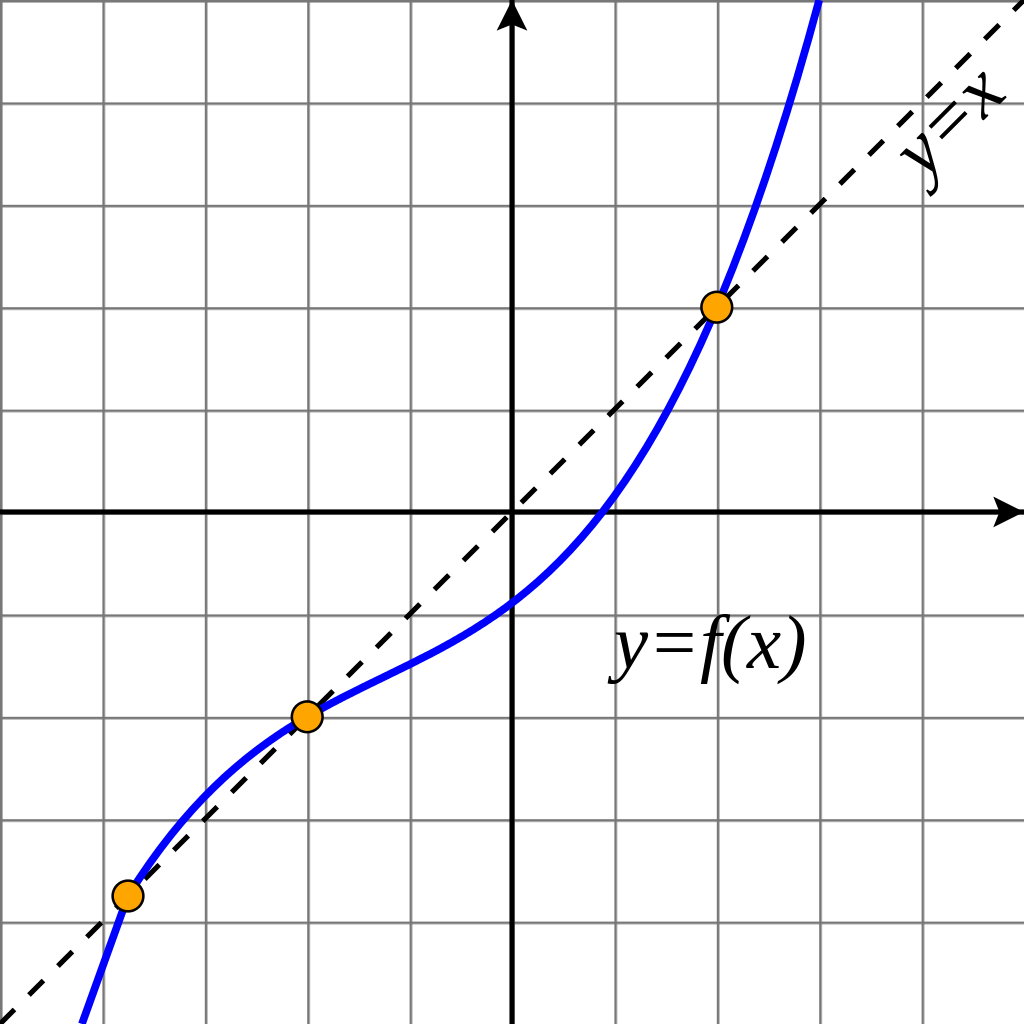

A fixed point of function \(f\) is a value that is mapped to itself by the function.2 In other words, \(x\) is a fixed point of \(f\) if \(f(x) = x\). For this to be possible, \(x\) has to belong to both the domain of \(f\) (set of values that it can take), and the codomain of \(f\) (set of values that it can return).

For example, if \(f(x) = x!\), 1 and 2 are fixed points, since \(f(1) = 1\) and \(f(2) = 2\).

The image shows the graph of a function \(f\), with 3 fixed points. When plotting with \(y = f(x)\), these 3 points were also on the line \(x = y\).

For example, for some functions \(f\), we can locate a fixed point by beginning with an initial guess and applying \(f\) repeatedly.

\[ f(x),\quad f(f(x)),\quad f(f(f(x))),\quad \dots, \]

We would do that until the value doesn’t change very much, and we are satisfied with the result.

5. Fixed-point combinators

A fixed-point combinator is a higher-order function (i.e. a function that takes a function as argument) that returns some fixed point of its argument function.3

So, if a function fix is a fixed-point combinator, a function f has one or

more fixed points, then fix(f) is one of these fixed points:

\[ f(\text{fix}\ f) = \text{fix}\ f \]

In lambda calculus, every function has a fixed point.

6. Y combinator

An example of a fixed-point combinator is the Y combinator. This is the definition of \(Y\).

\[ Y = \lambda f. \big(\lambda x. f (x\ x)\big) \big(\lambda x. f (x\ x)\big) \]

Or in Scheme:

(define Y (lambda (f) ((lambda (x) (f (x x))) (lambda (x) (f (x x))))))

Note: This version is not accurate, see Implementation in Scheme below.

Or in JavaScript:

var Y = (f) => ((x) => f(x(x)))( (x) => f(x(x)));

Since it’s a fixed-point combinator, calling \(Y\) with a function as its argument would be reduced to \(Y\ f = f(Y\ f)\). This is a very interesting and useful concept, and it’s where this image comes from.

Let’s try to understand what it does, and why it’s a fixed-point combinator. We are saying that \(Y\) is a function that takes one parameter \(f\). The body consists of the same lambda term applied to itself: \((\lambda x. f(x\ x))\). You may realize why we explained how to do recursion with anonymous functions earlier. A similar principle applies here, but we are also calling the \(f\) function.

Let’s simplify it with β-reduction step by step:

\begin{align*} Y\ g &= \lambda f. \big(\lambda x. f (x\ x)\big) \big(\lambda x. f (x\ x)\big) g && \text{By definition of } Y \\ &= \big(\lambda x. g (x\ x)\big) \big(\lambda x. g (x\ x)\big) && \text{By beta reduction: Replacing } f \text{ of } Y \text{ with } g \\ &= g \Big(\big(\lambda x. g (x\ x)\big) \big(\lambda x. g (x\ x)\big)\Big) && \text{By beta reduction: Replacing } x \text{ of the first function with } \big(\lambda x. g (x\ x)\big) \\ &= g (Y\ g) && \text{By equality} \end{align*}Note how the reduction on the third step is applying \(g\) to the same expression in the second step, which we know is equal to \(Y\ g\). That’s how we can verify that \(Y\ g = g(Y\ g)\).

An alternative (and slightly simpler) version of the Y combinator is the following:

\[ X = \lambda f. (\lambda x. x\ x) (\lambda x. f(x\ x)) \]

Notice how the first call to \(f\) was not necessary, since this expression also β-evaluates to the Y combinator.

7. Applications of the Y combinator

You might be wondering what makes the Y combinator so special. As we said, lambda calculus doesn’t have any kind of “global symbols”, therefore a function can’t reference itself by name. Let’s go back to the factorial example in Scheme.

(define fact (lambda (n) (if (equal? n 0) 1 (* n (fact (- n 1))))))

This recursive form is possible because the fact function can reference itself

by name. More specifically, because a lambda body is evaluated whenever a call

is made, and by that time the fact symbol is already bound to the lambda, and

therefore the body can reference it. In OCaml, for example, the rec keyword is

needed when defining a recursive function to denote that it will reference

itself, and not an external function with the same name.

The Y combinator allows us to call a function recursively in a language that

doesn’t implement recursion. Let’s have a look at an alternative form of fact.

(define fact-generator (lambda (self) ; Outer lambda (fact-generator) (lambda (n) ; Inner lambda (returned by fact-generator) (if (equal? n 0) 1 (* n (self (- n 1)))))))

Let’s carefully look at what we just defined. We are defining fact-generator as

the outer lambda, a function with one argument self. This function does not

return the factorial of a number, but instead returns another another lambda

function that will receive a number n, and return its factorial.

This inner lambda, the one that will be returned when calling fact-generator, is

essentially the same as our previous fact function, but this time it’s able to

use recursion without referencing itself by name by accessing the self parameter

of the outer lambda.

The important detail is that fact-generator is supposed to return a factorial

function, but also expects to receive a factorial function as its self

parameter, which will be used whenever the inner lambda wants to make a

“recursive” call. How could we accomplish this? At first sight, we could try

something like this.

;; Wrong. (define fact (fact-generator fact))

The code above is incorrect because of how Scheme evaluates the arguments. When

evaluating the define expression, it will first try to evaluate the call to

fact-generator, but before that it must evaluate its argument, the fact

symbol. Since at this point fact isn’t defined (we are trying to do just that),

Scheme will show an “Unbound variable” error.

Since the fact-generator function expects a function for calculating the

factorial, but also returns one, we are looking for something like:

(define fact (fact-generator (fact-generator (fact-generator ...))))

Does that look familiar? Indeed, this is just what the Y combinator allows us to do.

8. Implementation in Scheme

Our Scheme version of the Y combinator was not really correct. Evaluation in Scheme (and most Lisps) is strict, meaning that each argument is evaluated before applying the function. This is not a problem in lambda calculus.

8.1. Delaying evaluation with beta abstraction

Defining Y like we did before would result in infinite recursive calls when

trying to apply the (x x) expressions. This will be more obvious when analyzing

the combinator below, so let’s look at a possible solution first. We can fix our

Y combinator by beta abstracting4 those two applications.

JAO’s blog about the Y-combinator in Scheme (2014)

If you have a function

Fin Scheme, you can define a totally equivalent functionGby(define G (lambda (args) (F args))). We say thatGis a beta abstraction ofF, or thatFis a beta reduction ofG.The usual reason you would beta abstract a function in Scheme is in order to delay the evaluation of its body, just what the doctor ordered.

We can add this beta abstraction to the (x x) applications, effectively acting

as a “proxy”.

(define Y (lambda (f) ((lambda (x) (f (lambda (n) ((x x) n)))) (lambda (x) (f (lambda (n) ((x x) n)))))))

Now, since the (x x) expression is inside the body of this “proxy” lambda, it

will not be evaluated until the proxy is called. This is not easy to understand,

so so let’s try to visualize the evaluation process of a call to our Y function.

8.2. Evaluation process of our Y combinator

The following diagram represents the evaluation of a call to our Y

function. Specifically, applying the first inner lambda to its copy. Note that

this isn’t the actual process that a Scheme interpreter would follow, instead I

have decided to make some changes to make it easier to understand.

Let me explain briefly each step of the diagram.

- The black lambda receives a copy of itself (gray lambda) as the argument

x. We have seen this above with the \((\lambda x. x\ x)(\lambda x. x\ x)\) expression. - With some wishful thinking™, since we know that

xis a copy of the current expression, we can assume that the result of the green(x x)expression is whatever the current black expression returns. For now, it’s better to assume that the value returned when callingxisfact, since this will be explained in more detail below. - The blue

(lambda (n) (fact n))expression acts as a proxy, receiving some arguments, in this casen, and callingfactwith them. We name this simple lambdafact-proxy, since calling it is essentially the same as callingfact. - We know that

fis the function that has been passed toY, in this casefact-generator. We substitute it for readability, along with substitutingfact-proxywith justfact. - Finally, the expression

(fact-generator fact)gets passed to another lambda, or returned byY, depending on whether or not we are the first call in the recursive cycle.

At this point, although there are some parts that might not be very clear, we

can believe that (Y fact-generator) is the same as

(fact-generator (fact-generator ...)), which returns a recursive fact

function, even though fact has not been defined yet.

Now that we can see that the black expression effectively returns fact, you can

verify that the second point was true. The (x x) expression is calling x with a

copy of itself (the gray expression) as argument. That argument will be used for

looping recursively, as mentioned in point one. Therefore, the call to x returns

fact, and that’s why we were able to replace it on point two.

By wishful thinking, we know the (x x) call returns fact, but since evaluation

in Scheme is strict, it will try to evaluate the call to x, which also contains

another call to x, and so on. That’s what the fact-proxy is for.

With this example, you can also realize that the following expression makes more sense now.

\begin{align*} Y f &= f (Y f) \\ &= f (f (f (\dots))) \end{align*}Which is just what we wanted to achieve earlier.

(define fact (fact-generator (fact-generator (fact-generator ...))))

8.3. Complete Scheme example

Finally, we can try our full example.

(define Y (lambda (f) ((lambda (x) (f (lambda (n) ((x x) n)))) (lambda (x) (f (lambda (n) ((x x) n))))))) (define fact-generator (lambda (self) (lambda (n) (if (equal? n 0) 1 (* n (self (- n 1))))))) (define fact (Y fact-generator)) (fact 5)

9. Final note

If you reached this far, I hope you have learned something. Everything in this article is based on what I found while trying to learn about the Y combinator, so if you feel like some explanations could be improved, feel free to contribute.

Footnotes:

The exact differences between the Lisp and JavaScript editions can be checked in this website, which has been very helpful.

See the Wikipedia page for fixed point.

See the Wikipedia page for fixed-point combinator.